Last summer, the World Health Organization’s Regional Office for Europe released a report showing an alarming decrease in condom use among young people. The report relied on data from the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study which surveyed over 242,000 15-year-olds across 42 countries and regions between 2014 and 2022.

Among other things, the survey found that the proportion of sexually active adolescents who used a condom at last intercourse dropped from 70% to 61% among boys and from 63% to 57% among girls between 2014 and 2022. The report also found that almost a third of adolescents (30%) used neither a condom nor the birth control pill at last intercourse.

This drop in condom use is not unique to Europe. A study earlier last year in the U.S. found an increase in condomless anal sex among men who have sex with men who were not on PrEP. And in October, the Associated Press released a report that blamed dropping condom use among American young people on the promotion of new prevention methods and the lack of sex education.

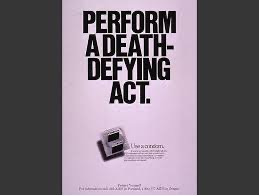

At the time, I started formulating an article about how public health had abandoned the condom and why we should go back to old-fashioned condom promotion ads like these.

Of course, before I actually wrote said article, we abandoned public health. In the wake of cancelled cancer research, mass layoffs at the CDC and NIH, censored web pages, and the deliberate undermining of vaccines, suggesting posters with sexy couples and cute taglines seemed silly. But I still think there’s a germ of an idea here (pun inadvertent but cute).

When I started in this field, condoms were our bread and butter. We talked about them ad nauseum and with good reason. HIV was not the manageable disease it is today. We had some medications that could keep people with HIV from developing AIDS in the near term, but the cocktails were cumbersome, the side effects were rough, and the slide into bad health was always looming. In short, HIV was still terrifying, and condoms were the only protection.

The scientific progress we’ve made in the field of HIV has been tremendous. Today’s medication is easier to take, easier to tolerate, and it works. People who stay on antiretroviral therapy (ART) can reach a point where the virus is undetectable in their blood. This not only keeps them healthy but also prevents them from transmitting HIV to a partner regardless of whether they’re using a condom. HIV treatment is now also HIV prevention because undetectable = untransmissible.

Moreover, we now know that using some of these very same drugs can protect people who don’t have HIV from getting the virus. When used correctly Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) can be 98% effective in preventing the sexual transmission of HIV. PrEp was introduced in 2012 as a daily pill and experts wondered if healthy people would stick to the regimen. Though PrEP use is still not as widespread as it could/should be, people do stick to the regimen and there are newer versions that are given as an injection every other month. By the end of this year, we might have a version of PrEP that is nearly 100% effective and only needs to be given twice a year. (It’s not a vaccine but acts like one. What will RFK, Jr., say to that?)

All of this progress on HIV prevention is fantastic, but it has put a strain on condom messaging. For one thing, public health experts tend to promote the method that works the best and there’s no denying how well PrEP works. For another, much of our condom messaging was built on an undercurrent of fear. We didn’t exactly say “use this or die” out loud, but it was what most people heard. When the “or die” part went away, “use this” seemed to follow.

We tried to remind people of the perpetually rising rates of other STIs like chlamydia or gonorrhea, but penile discharge and an itchy vadge don’t pack the same punch especially once you add the phrase “cured by antibiotics.” Even the threat of antibiotic-resistant gonorrhea didn’t seem to make waves. And then we got Doxy PEP which is to bacterial STIs what PrEP is to HIV (only not quite as effective).

Doxy PEP is for people—mostly men who have sex with men—who are at increased risk of bacterial STIs. They can take the antibiotic doxycycline before sex to prevent infection. It is about 80% effective against syphilis and chlamydia. It’s only 50% effective against genital gonorrhea and even less against gonorrhea infections of the throat, but that’s still pretty good given how common this STI is.

It’s not surprising that attention and resources shifted away from condoms when public health got these new bright shiny toys. It takes a lot to raise awareness of a prevention method when you’re starting from scratch. People need to be told that PrEP and PEP even exist. Condoms have been around for hundreds of years; they have name recognition. Also, sex educators like me have been talking about condoms for hundreds of years, it’s kind of fun to turn our attention to something new.

We did a similar thing with contraception, too. Condoms are a workhorse method. They’re always available, easy to use, easy to get, and cheap. They take minimal advanced planning. Generations of young people used condoms as their first method of contraception and enjoyed the STI prevention benefits that came with. Condoms can be excellent birth control, but they are user-intensive, and users are known to make mistakes (mostly not using one “just this once”).

So, with good reason, sex educators like me started promoting long-acting reversible contraception (LARCs) like IUDs and implants that work for years without any effort on the part of the user. Of course, we mentioned that these methods don’t protect against STIs and suggested using condoms anyhow, but even we doubted people would do it. (Young people tend to fear pregnancy far more than STIs.)

Condom promotion fell away as we pushed all of our new acronyms – PrEP, Doxy PEP, and LARCs. I would also argue that some of this pivot was based on the general negativity that seems to surround our most basic condom messaging.

This is some of what Logan Levkoff and I wrote about in our 2021 article, “We’re Teaching About Condoms All Wrong: How Sex Educators Reinforce Negative Attitudes and Misinformation About Condoms and How to Change That,” which was published in the American Journal of Sexuality. Even those of us who want people to use condoms tend to walk into every classroom, patient education session, or campaign planning meeting with the assumption that people already hate this method. (And we do this even if our audience is 12-year-old virgins who have never seen a condom.)

It wasn’t always like this. Condoms were once revered or at least celebrated. Ancient Chinese societies made them out of paper and leather. Italians in the 1560s made reusable ones out of linen with ribbons that could be used to tie it onto a penis. In 17th century Japan you could get one made out of tortoise shell. These were considered important inventions to help people avoid syphilis which has been around since at least the 1400s and was not curable until the 1940s.

Last week a 200-year-old condom went on display at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. (Before you get worried or grossed out, curators looked at it under a CSI style UV light and determined it was unused.) The sheath, which likely dates back to 1830, was made of sheep intestine.

This is not unusual. The practice of using animal intestines to make condoms goes back to the Ancient Romans, and if you have $15.99 and an Amazon Prime account, you could have a three pack of Trojan NaturalLamb on your doorstep by tomorrow. (These new ones work well against pregnancy but are not as effective against STIs—especially HIV—because it turns out that lamb intestines are more porous than latex or polyurethane. I would not recommend relying on one from previous millennia.)

What’s unusual about this condom is that it’s decorated. There is an intricate print on it that depicts three clergymen standing in front of a nun who is sitting down. All of them—including the nun—have lifted their habits to show what they have underneath. She is pointing at them. (I’d like to think she’s laughing but there’s not quite enough detail in the face to be sure.) There is also writing on the condom that says, “Voilà mon choix,” which means “there is my choice." (So maybe she’s not laughing, she’s just picking a favorite penis.)

Curators, who are known to overanalyze, say that the print “embodies both the lighter and darker sides of sexual health, in an era when the quest for sensual pleasure was fraught with fears of unwanted pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases – especially syphilis." They also believe the picture is a “parody of both celibacy and the Judgement of Paris from Greek mythology” The condom itself is thought to be a “luxury souvenir” from a fancy Paris brothel.

I’ve also been known to overanalyze, but I fear I’m getting this one right. Public health abandoned the condom out of fears that everyone hates them and faith in newer prevention methods for both STIs and pregnancy. The problem is that many of those prevention methods are only appropriate for some people and all of them take far more advanced planning than picking up a pack of condoms at CVS or 7/11.

I would like to see public health come back to the simple condom and give it the place it’s earned over the last several centuries. On display in a museum is great, but on penises everywhere would be better.

Bonus Flashback Story: Hamster Sex

Sometimes when I write about a topic I’ve been writing about for decades like condoms, I spend too much time looking back in my files. I’m convinced I said something perfectly in another document and that plagiarizing myself will be easier than just writing something new. It rarely is, but the trip down memory lane can be a fun form of procrastination.

As I was working on this, I found a story I wrote for Rewire News in 2011 saved in my archives as hamstersex.doc. Of course I had to open it.

It was long before I started writing Sex On Wednesday, but I was apparently just as snarky. (It was also before we went to one space after a period, and I was still using Garamond for all my Word docs. I love that font, but it’s no longer bold enough for my old eyes.)

I thought I’d share.

Okay, so I had literally just finished posting my last news story about how teens are behaving responsibly when it comes to contraception and the birth rate is coming down, when a story with this headline popped up in my in-box: “Teen Sex May Affect Brain Development, Study Suggests.”

The article, from Fox News (of course), began by discussing the uproar over a recent episode of Glee in which two teen couples have sex for the first time. I missed the uproar because in my circle of friends the episode was happily received as a rare, positive portrayal of teen sexuality. But not everyone saw it that way. The watchdog group, Parents Television Council denounced the episode in a statement before it aired, saying: “The fact that ‘Glee’ intends to … celebrate children having sex is reprehensible.” I suppose that was inevitable.

Anyhow, this article goes on to say that the uproar may have some “scientific legs.” You see, it explains, “new research shows sex during the adolescent years could affect mood and brain development into adulthood.”

Interesting. I read on.

“The study, which was carried out on hamsters, reveals how social experiences during adolescence when the brain is still developing can have broad consequences.”

Hamsters?

Yep. Hamsters.

Apparently, scientists compared three groups of hamsters on their 120th day of life: the first group had mated with an adult female in heat when they were 40 days old (roughly the equivalent of human teens because hamsters hit puberty at 21 days); the second waited to mate until they were 80 days old, and a third control group was not exposed to females at all (sorry guys).

At the 120 day mark the researchers found that the hamsters that had become sexually active at 40 days were more likely to stop swimming vigorously when placed in water than their peers in the other groups. This was described as a symptom of depression. These hamsters also showed less “complexity in the brain’s dendrites” and had smaller seminal vesicles and vas deferens. On the plus side they had lower body masses and enhanced immune responses.

Researchers also found that “all of the sexually active hamsters showed higher levels of anxiety, measured by willingness to explore a maze, than the virgin hamsters.”

While this does sound like bad news for the hamsters—and definitely fodder for those arguing for celibacy among rodents—I don’t see how it is bad news—or news at all—for human teens. And neither do the researchers. The study (which was presented at a professional meeting but has yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal) joins a growing body of research studying the impact of hormones on brain development in animals. But the lead researcher cautioned against direct correlations with humans: “In no way do these data bear directly on the issue of teenage abstinence.”

Of course, that didn’t stop Fox from suggesting otherwise in its headline.

Some things never change.