The 2023 Nobel Prize in Economics was awarded this week to Claudia Goldin, a Harvard economist who has studied the changing role of working women in modern history and the causes of the pay gap between men and women. Some of Goldin’s well-known work includes her analysis of how the birth control pill changed the course of women’s lives for the better.

When Margaret Sanger and her colleagues set out to create the birth control pill, this was exactly what they wanted to do. It wasn’t simply about finding a new way to prevent unintended pregnancy for individual women, it was about advancing all women by allowing them to plan their reproductive lives, which could in turn free them up to plan their professional lives. There are a lot of negative things that can be said about the invention of the pill—from questioning whether Margaret Sanger’s motives were rooted in eugenics and racism, to condemning the experiments done on Puerto Rican women without their informed consent—but the pill really did change the world, and Claudia Goldin helped explain how.

(For anyone who is interested in the pill’s development, I highly recommend Jonathan Eig’s book, The Birth of the Pill. And for anyone who is interested in the pill’s development but not interested enough to read a whole book, I highly recommend the Cliff’s Notes version which is Terry Gross’s Fresh Air interview with Jonathan Eig.)

The pill was approved by the FDA in 1960, and within five years about half of married women were already using it. The real revolution, however, didn’t take place until the early 1970s when a significant portion of unmarried women began taking the pill as well. (We’ll get back to why this took so long a little later). In a 2002 article, “The Power of the Pill: Oral Contraceptives and Women’s Career and Marriage Decisions,” Goldin and her colleague Lawrence F. Katz note that in 1970 just 10% of first year law students were women, but by 1980 that percentage had gone up to 36%. They go on to explain why the pill should get much of the credit for this, and it’s a little more complicated than “they didn’t get pregnant, so they had time to become a lawyer.”

Goldin and Katz explain that before there was a reliable, female-controlled method of contraception, women had to factor an accidental pregnancy into their career planning. Going into a field like medicine or law that would take five or more years of training was a risky move. If they did get pregnant, they could lose all of the time and money they’d invested in their education. Many women, whether consciously or unconsciously, decided it wasn’t worth the risk and limited their professional aspirations.

There was another aspect of this career calculus as well. Choosing to go into one of these fields with a long ramp-up period, often also meant choosing to delay marriage. As many of their mothers likely pointed out every year at Thanksgiving dinner, this is risky. If you wait until you’re—gasp—30, all the good men will be snatched up by less ambitious women. There will be no one left to marry. You could become an old maid or, worse, a spinster. (Which is actually worse? Is there a difference?) The pill changed that, too. Everyone started marrying later—even women who weren’t using the pill—and this meant that there would still be eligible husband material after med school and residency.

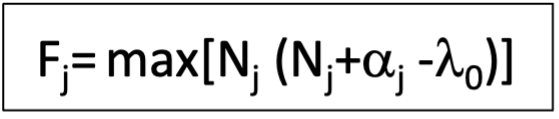

Goldin and Katz offer complicated calculations—they are economists after all—of how the pill changed the marriage market which rest on this equation:

The variables include career abilities and the impatience factor. I got an A+ in my symbolic logic class in college (turns out I’m good at math as long as there are no numbers involved), but I’m not going to pretend I understand their calculations. What makes perfect sense to me, however, is what they say about the growing acceptance of premarital sex:

“The pill enabled young men and women to put off marriage while not having to put off sex. Sex no longer had to be packaged with commitment devices, many of which encouraged early marriage.”

No one is arguing that the pill was the only thing that changed social mores in the 1970s. There was a lot of other stuff going on at the time—including the Vietnam War—but Goldin and Katz make a strong case for the role of oral contraceptives. They tracked the pill’s availability state-by-state and found that as each state made it more available to young women, marriage age, female enrollment in professional courses of study, and women’s wages all increased.

This brings us back to why it took more than 10 years for the pill to start changing lives: Comstockery. (I wish I could take credit for that word because I love it almost as much as I love assholery, but it comes directly from Goldin and Katz’s article.) They refer to the Comstock Act itself—the one that made it a crime to mail “lewd” material from porn to sex education pamphlets to contraceptive methods—as unimportant but acknowledge that it led to a series of state laws that limited access to contraception. In 1960, when the pill was approved by the FDA, 30 states prohibited advertising birth control, and 22 had some sort of prohibition on who could buy contraception. Most of these laws were directed at young, unmarried women—precisely those who needed the pill the most.

Over the next ten years or so, access to contraception improved. Some states decided to change their laws and others were compelled to do so after a series of Supreme Court decisions. In Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), the Supreme Court ruled that states could not limit the rights of married people to access contraception. In Eisenstadt v. Baird (1972), SCOTUS extended access to contraception to unmarried people. And, of course, the following year Roe v. Wade (1973) recognized women’s right to abortion.

It was this increased access to reproductive health tools that helped women plan pregnancy and therefore plan their lives. It is this increased access to reproductive health tools that we are now in the process of losing.

Roe v. Wade has already fallen, and women in states around the country can no longer access safe, legal abortions. Call me a conspiracy theorist, but contraception is next. Clarence Thomas all but said so in his concurring opinion in Dobbs v. Jacksons Women’s Health (2022) when he argued that the Court had to extend the logic it used to overturn Roe to other cases that rested on the same privacy principal. Griswold was one of the cases he named. His buddy Samuel Alito laid groundwork for dismissing the pill and other contraceptive methods as abortifacients in the Hobby Lobby v. Burrell (2014) decision in which he argued it didn’t matter what the science said about these methods, it only mattered what the plaintiffs believed.

And then there’s the Comstock Act which, it turns out, is not unimportant even 150 years later. In fact, this act is at the center of a court case that will ultimately decide if mifepristone—one of two drugs used in a medication abortion—can be sent through the mail. That decision will have a huge effect on access to abortion everywhere in the country, even in states where abortion remains legal. (Please see Anthony Comstock Continues to F**k Us All for my take on the man and his law.)

For as long as women have had access to the pill and safe abortion, we have been fighting to keep that access, and Claudia Goldin’s work explains why. Access to the pill and safe abortion gave women power. It gave us the power to have sex without getting pregnant, the power to choose further education and better paying jobs, and the power to support ourselves without men. Clearly, there are still forces in this country who would rather we not have this power, independence, or sexual agency.

Anti-abortion arguments have always been couched in “save the babies rhetoric,” and arguments against contraception will likely rest on calling them abortifacients, but we should all recognize that the push backwards has always been about taking the power of reproductive freedom away from women.

I wonder if the Nobel Prize committee is sending us a message with this award. In Norway, birth control is available for free for those under 20 and abortion is legal through the first trimester. The country also takes better care of those who choose to become parents, offering 12 months of leave per kid per parent. Adoptive and foster parents have these same rights. When Nobel Prize committee member Randi Hjalmarsson said, "Claudia Goldin's discoveries have vast society implications," do you think he was talking about his country or ours?

Congratulations to Claudia on winning the The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel. She deserves the recognition and the 11 million kronor (about $1 million) that comes with it. Of course, there is further proof that Goldin’s research is important: she’s only the third women to ever win this prize.

Wow, thank you! This made my day.

It was always so clear to me that anti-abortion movements are never about the fetus. But had I thought they were mostly about preventing women from fully expressing their sexuality. Your essay describes another set of reasons that explain anti-abortion fears with more depth and complexity. Thanks so much for this.